The US immigration system disproportionately impacts people from India who are contributing to the US economy. Sital Kalantry, a law professor, associate dean and director of the RoundGlass India Center at Seattle University School of Law and Stephen Yale-Loehr, a professor of immigration law practice at Cornell Law School and faculty director of its immigration law and policy program point out the problems Indian workers face. PRAVASI SAMWAD reproduces their article which appeared in the SEATTLE TIMES.

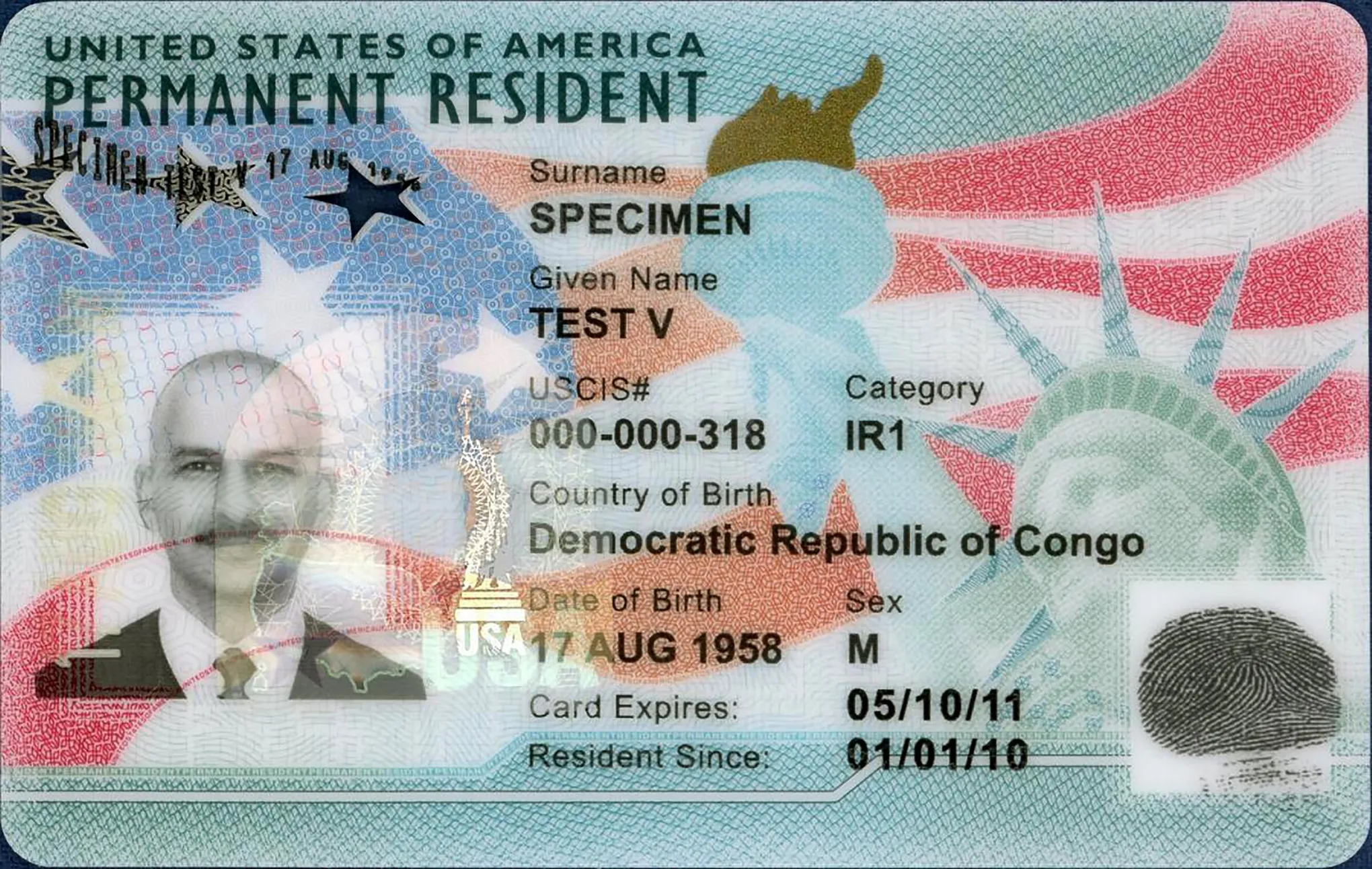

Each year, the United States issues 140,000 green cards based on employment. However, these green cards, which allow someone to live and work permanently in the U.S., are not allocated on a first-come, first-served basis. As a result of antiquated rules, green cards are capped; people from no single country can receive more than 7% of the annual employment-based green card allotment.

India has the largest population in the world. That, plus the focus on science, technology, engineering and math education in India, has led to a disproportionate number of people from India (as opposed to people from other countries) living in the United States. People from India now represent the second-largest population of foreign-born people in Washington.

Many people from India work on H-1B temporary visas, but that visa does not provide a direct path to permanent residency. (The EB-2 and EB-3 employment-based green card categories provide a path to permanent residency.)

The Cato Institute estimates that 1.1 million Indians are in the green card backlog in the employment categories. While people from other countries like Canada can receive employment-based green cards relatively quickly, some Indians starting the green card process now may face a wait of over 130 years.

The consequences are dire for people from India who have spent a significant portion of their lives here and whose kids may have grown up here, for several reasons:

First, the Cato Institute estimates that more than 400,000 people from India who have helped our economy grow and have lived most of their lives in the United States will die before they get permanent residency.

Second, over 100,000 children of Indians will become undocumented if they remain in the United States when they turn 21 because they can no longer get a green card through their parents. To avoid becoming a “documented dreamer,” these children who have been raised in the United States have to return to India while their parents remain here to keep their place in the green card line. This unfairly separates families.

The issue appears to be stalled along with a much broader and needed immigration reform in this country. In the meantime, immigrants from India and their employers pay the price of our broken immigration system

Third, many Indian employees at U.S. companies are trapped in jobs that may not pay well or treat them fairly. An employer typically sponsors an employee for a green card. If the worker switches employers, they must start the green card process all over again, which puts them at the back of the long queue. This is problematic for employees waiting for a green card, as it restrains their freedom of employment and movement. For anyone else, this would be a violation of human rights, but for workers from India, it is seen as business as usual.

The idea that we should place green card limits on a per-country basis rather than treat everyone equally dates back to 1924, when eugenics had currency and the vision of America as a Caucasian nation prevailed. This prevented many nonwhite people from entering the United States. This changed in 1965, when Congress ended an immigration admissions policy based on race and ethnicity. However, per-country limits remained for employment-based green cards. Most immigration scholars recognize the racism in such quotas.

Employers have lobbied to change the per-country limits, as it harms them when they are not able to bring skilled workers into the United States when there is a domestic shortage. It deters highly skilled people from India from seeking entrance into the United States, given the long backlog they face. The most devastating impact is on the Indian employees themselves and their children.

In 2020, Congress came close to fixing this problem. The House and Senate each passed a bill to remove the per-country limits, but the chambers were unable to resolve the difference between their two versions. There was also a push to increase the annual number of employment-based green cards from 140,000 to 270,000.

Today, immigration is more controversial than ever. Some Republicans oppose any increase in immigration. Some Democrats worry that would-be employees from Africa would have to wait much longer if Congress eliminated country-based caps. However, no country in Africa currently meets its annual quota for employment-based green cards.

Sadly, this issue appears to be stalled along with a much broader and needed immigration reform in this country. In the meantime, immigrants from India and their employers pay the price of our broken immigration system.

************************************************************************

Readers