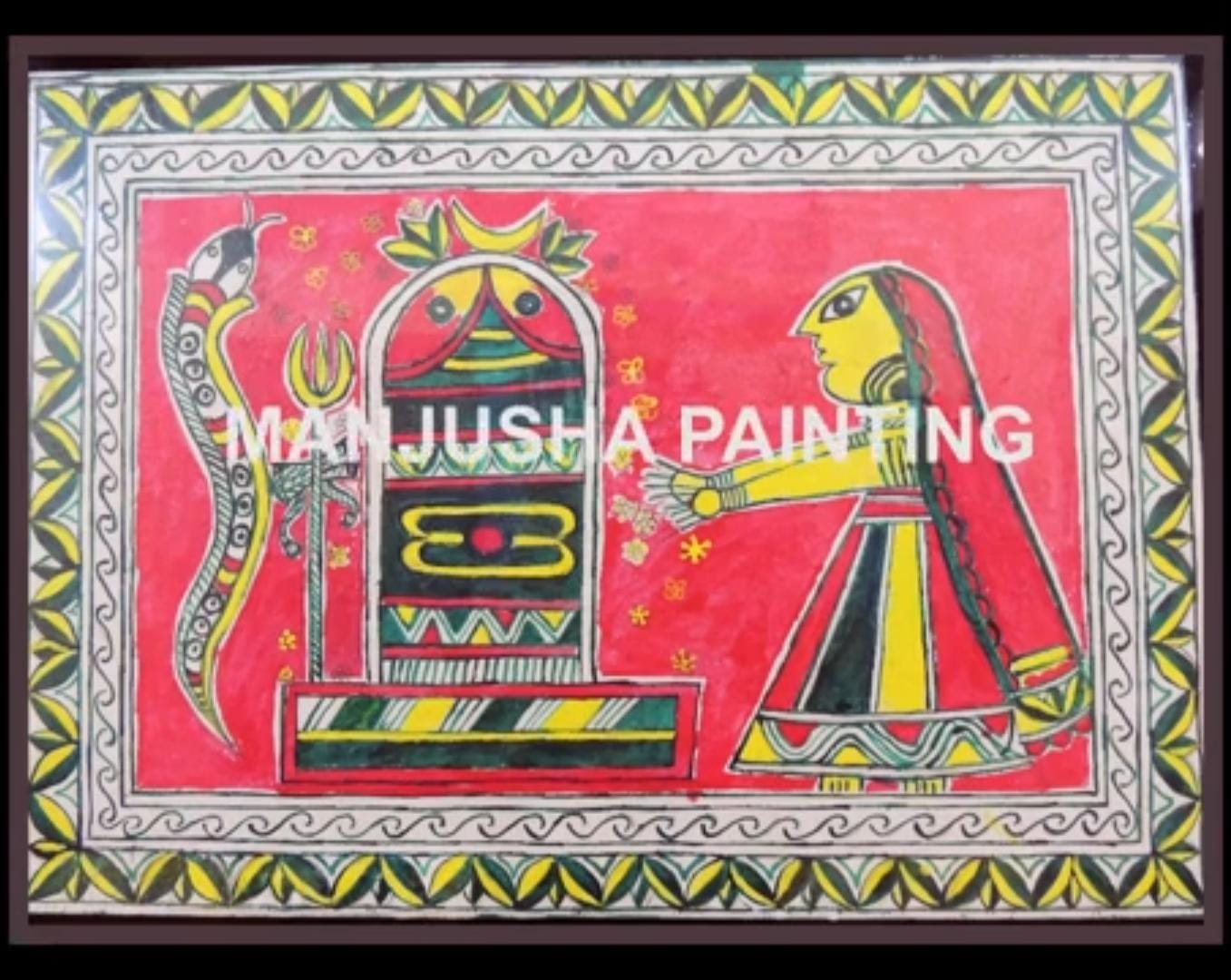

In Sanskrit, “Manjusha” means “box.” This term refers to ceremonial temple-shaped containers crafted from bamboo, jute straw, and paper, which devotees use during Bishahari Puja to store various items

Fifty-five-year-old Manoj Pandit is painting, not a wall or a canvas. Rather, he is adorning the coaches of a train with Manjusha art. This train, with its colourful artwork, will glorify this art form as it ferries passengers from one end of Bihar to another.

Originating in the 7th century, Manjusha art now graces the exteriors of a significant train route linking Bhagalpur in Bihar to the Anand Vihar Terminus in New Delhi.

In Sanskrit, “Manjusha” means “box.” This term refers to ceremonial temple-shaped containers crafted from bamboo, jute straw, and paper, which devotees use during Bishahari Puja to store various items. The Manjusha boxes hold symbolic importance, representing the container that legend says covered the body of Bala Lakhendra in the folklore of Bihula-Bishahari. According to the tale, the temple-shaped box, known as Manjusha, was adorned with Bihula’s narrative, depicting the flora and fauna of Anga, thereby marking the origin of the art form bearing the same name. To grasp the significance of Manjusha art, one must delve into the folklore surrounding Bihula-Bishahari.

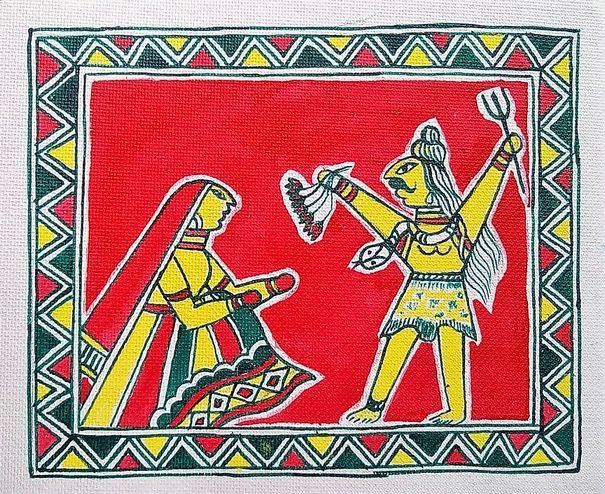

The folktale that inspired the Manjusha Art tells the story of Bihula and the snake goddess Bishahari, also known as Mansa, saving her husband from divine wrath and snakebite. This story, which was originally passed down orally, describes Shiva’s encounter with five lotuses that become five sisters.

Accepting them as his daughters, Shiva gives them powers and names them Bishahari. After resurrecting Goddess

Parvati, the sisters are accepted after first being rejected. But they curse the family of a pious businessman named Chando Saudagar when he refuses to worship them. Bihula’s fortitude is revealed in the face of ensuing catastrophes, such as the passing of Chando Saudagar’s son. She sets out on a quest to bring her husband back to life, facing obstacles along the way and praying for divine help.

Originating in the 7th century, Manjusha art now graces the exteriors of a significant train route linking Bhagalpur in Bihar to the Anand Vihar Terminus in New Delhi

In the end, she obtains blessings for the happiness of her family, provided that Chando Saudagar worships Bishahari. Initially reluctant, eventually complies under divine guidance, ensuring the family’s redemption and prosperity.

In the story, five hairs from Lord Shiva’s plait change into five lotuses while he bathes in Sonada Lake. These lotuses beg

Shiva to accept them; each one stands for a daughter. When Jaya, Dhothila Bhavani, Padmavathi, Mynah, Maya, and Jaya Bishahari reveal their true forms as five sisters, Shiva takes them in as his daughters, referring to them as “Manasaputri” or adopted daughters. When they approach Goddess Parvati for acceptance, she first declines. When she goes to pick flowers, they bite her out of agitation, knocking her out cold. Shiva steps in and promises Parvati that she will accept, which prompts Jaya Bishahari to use nectar from her vessel to bring her back to life. Then, Parvati bestows upon them a boon that releases them from the poison of their snake forms; they are now referred to as “Bishahari.”

“It is majorly a line drawing art with the characters displayed as X letter of English Alphabets.” says the famous artist Manoj Pandit from Bhagalpur

The significant motifs in this art form include the snake, Champa flower, sun, moon, elephant, turtle, fish, Maina bird, Kamal flower, Kalash pot, arrow bow, Shiv Ling, and tree. Among the prominent characters depicted are Lord Shiva, Mansa Devi (Bishari), Bihula, Bala, Hanuman, and Chandu Saudagar.

Borders play a crucial role in Manjusha paintings. The artists commonly utilized motifs for borders include leheriya, sarp ladi, tribhuj, mokha, and belpatra. Additionally, artists occasionally incorporate a solid band of yellow, green, or pink colour following these motifs to enclose the painting, giving it a sense of completion.

“The process of creating this art form begins with a ritualistic approach. When initiating a painting for religious purposes, I start by forming a pile of rice in the room. Atop this pile, I carefully place a betel leaf with a betel nut and pray for permission from the goddesses to commence the painting. The moment the leaf shifts or falls, I interpret it as a sign granting permission to begin my work,” says the popular artist Shrimati Nirmala Devi who was awarded with Bihar Kala Award ‘Sita Devi Award’.

Whenever Manjusha art is discussed, it’s impossible to overlook Shrimati Nirmala Devi, recipient of the Bihar Kala Award, also known as the Sita Devi Award.

“After the ceremonial process of seeking permission, I begin by outlining the painting before applying colors. Traditionally, the outline is sketched in green, although modern artists may opt for black. Historically, rulers and other precise tools were eschewed to preserve the art’s raw authenticity, with imperfections considered to enhance its allure. However, contemporary practices involve the use of various instruments to achieve symmetry and precision in the paintings,” says the artist.

The Belpatra motif is commonly used to represent the leaves of the bel tree, which are devoutly offered to Lord Shiva and are believed to hold great significance to him. Leheriya symbolizes the flow of the river and the ripples created when Bihula transported her husband’s body in a boat adorned with Manjusha. Sarp ladi represents the collective presence of snakes commanded by Goddess Manasa, while mokha originates from the Manjusha bhitta chitra.

The ‘kalash’, derived from the ‘amrit kalash’ of the Bihula-Bishahari folktale, serves as a recurring motif in Manjusha art during Bishahari Puja.

All characters depicted in Manjusha paintings exhibit a distinctive style. Human figures are represented by the letter ‘X’, with limbs raised. Major characters are depicted with large eyes and without ears.

Presently, numerous artists in Bhagalpur and Patna are dedicated to advancing the success of this art form. Among them, Ulupi Jha, a Bhagalpur resident and a committed artisan in this field, has been recognized by the Ministry of Women and Child Development as one of the 100 accomplished women in India. Collaborating closely with the state government and the Upendra Maharathi Shilp Anusandhan Sansthan (UMSAS), she orchestrates training workshops for artisans to keep this artform alive.

***********************************************************************

Readers

These are extraordinary times. All of us have to rely on high-impact, trustworthy journalism. And this is especially true of the Indian Diaspora. Members of the Indian community overseas cannot be fed with inaccurate news.

Pravasi Samwad is a venture that has no shareholders. It is the result of an impassioned initiative of a handful of Indian journalists spread around the world. We have taken the small step forward with the pledge to provide news with accuracy, free from political and commercial influence. Our aim is to keep you, our readers, informed about developments at ‘home’ and across the world that affect you.

Please help us to keep our journalism independent and free.

In these difficult times, to run a news website requires finances. While every contribution, big or small, will makes a difference, we request our readers to put us in touch with advertisers worldwide. It will be a great help.

For more information: pravasisamwad00@gmail.com