Latay has followed four Indian families in different parts of the country that have been waiting several years to get green cards despite their significant contributions to the American Academy, economy, and society

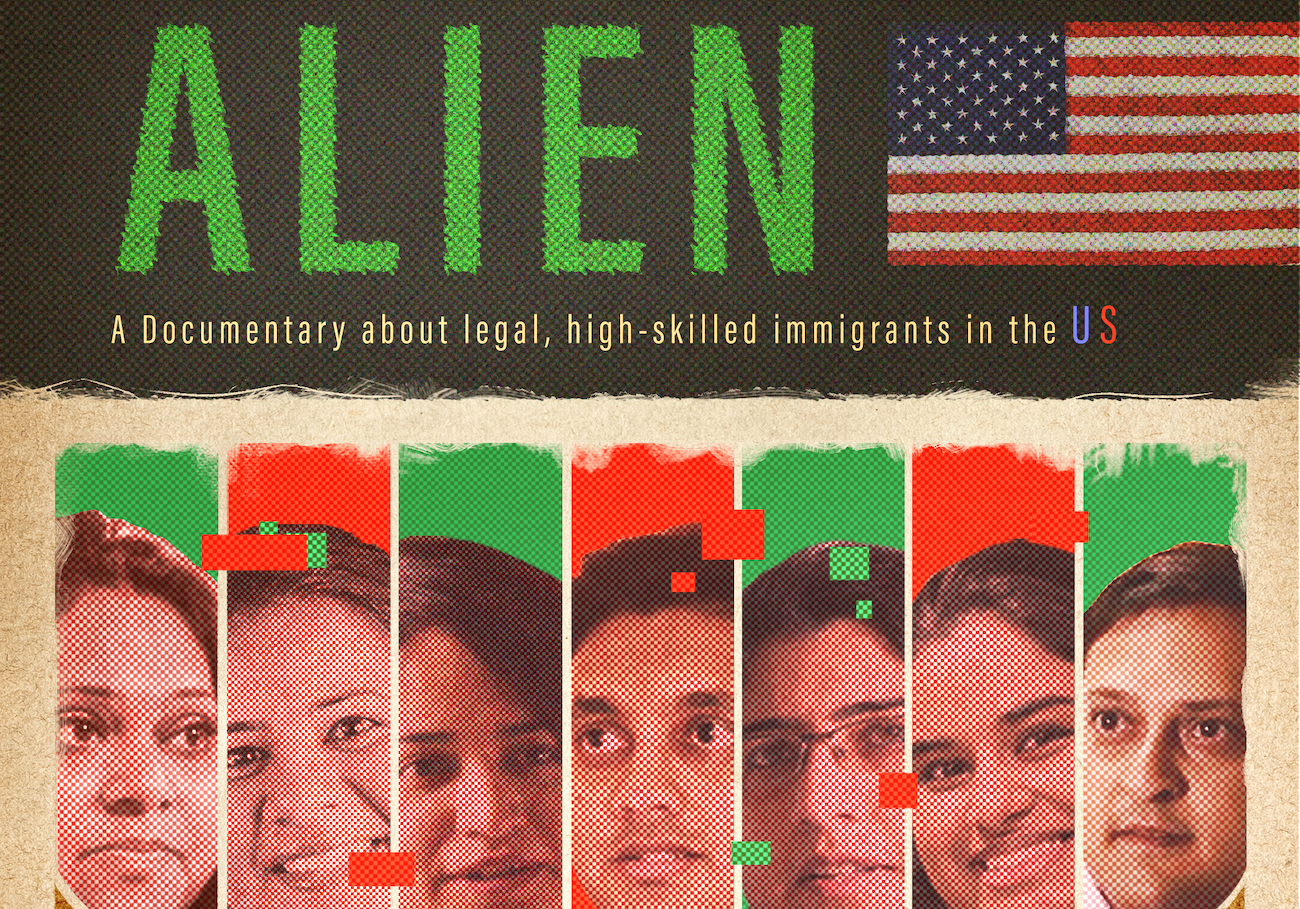

Director Vidut Latay’s documentary film “Alien” (2023) will be featured at the Oscar-qualifying Tasveer 2023 South Asian Film Festival, October 12-22. The film transforms American understanding of the hardships of Indian high-skilled migrants and their dependents by identifying the fraught U.S. immigration system that enables the exploitation of Indian migrant labor by American corporations, according to a report in americankahani.com.

Latay has followed four Indian families in different parts of the country that have been waiting several years to get green cards despite their significant contributions to the American Academy, economy, and society. Latay documents these skilled professionals’ loss, anxiety, experience of alienation, and inhuman treatment at the hands of the US Immigration Services.

The four H-1B and H-4 families waiting for green card status, Vakkalanka/Royyuru, a doctor couple in Bloomington, Illinois, with two H-4 dependent teenagers in fear of aging out; Lopa Mathur, H-4 dependent in Pacific Northwest, a clinical psychologist and a community activist protesting against the green card backlog for the Indians; Sadhak Sengupta, the H-1 B academic at Brown, and his dependent wife, Sudarshana Sengupta, an H-4 holding cancer researcher; Girish Chavan and Ketaki Desai, H-1B visa holder couple from Pittsburg, Pennsylvania; and Sunayana Dumala an H-4 dependent from Olathe, Kansas, the wife of Srinu Kuchibhotla, who lost his life to a hate crime in 2016.

The South Asian community Latay documents experiences legal and economic marginalization, and their future is bleak. However, change can only come with acknowledgment of the issue first

Latay interviewed these families during COVID-19, conducted at the respondents’ homes and workplaces, with casual conversations in the park or car, presenting the respondents’ family, professional, and social lives.

The H-1B visa is a temporary visa tied to specialty occupations in science, technology, engineering, and medicine. A company looking to hire H-1B applicants registers the applicants’ details with the U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services (USCIS). The H-1 B worker has to stay with the same employer to file the petition for a green card, the ticket to acquiring permanent residency in the country. If an immigrant changes jobs, the new employer must apply for H-1 B on the employee’s behalf. Each year, 85,000 H-1B visas are allotted, and around 75% of those go to professionals from India.

The US issues 140,000 employment-based green cards each year. Under the 1990 immigration Act, no country can receive more than 7% (around 9,800) of total employment-based and family-supported green cards annually. 1.5 million people are waiting for the 7% green card/ permanent residency, and 82% of these applicants are from India. The green card backlog is nearly ten times the number of green cards available for employment-based immigrants.

More than 200,000 Indian immigrants are stuck in the backlog and will probably die before they get their green card.

- Latay focuses on the inability to work because of the visa status of millions of spouses and children of the H-1B holders through the lives of Dr. Lopa Mathur, Ketaki Desai, and Sudarshana Sengupta

- These women, all having master’s or Ph.D. degrees, discuss at length the dependency forced upon them by the H-4 visa

- Unable to have finances, careers, and even identities of their own, these women are obligated to put their lives on hold and be subject to the worst form of patriarchy in the US

Latay poignantly shows the suffering of the Indian immigrants as they face the realities of the backlog. Sadhak Sengupta, Ph.D., applied for his green card in 2010 and has not been to India since 2012 because of the visa waiting. His wife, Sudhesana Sengupta, lost her mother in 2011 but could not return to India for fear of being unable to return and losing her family.

The film highlights the uncertainty, strain, and stress-inducing race to green card status all H-1B and H-4 visa holders undergo at the mercy of their employers, who must sponsor this process of migrants to obtain permanent residency in the United States.

Contrary to the popular claim, all four couples argue that they do not take away American jobs, citing numerous employers lobbying to increase the H-1B quota only to deny a parallel increase in green cards. They say the green card backlog is a human rights issue; they remain foreigners and are treated as commodities.

Latay focuses on the inability to work because of the visa status of millions of spouses and children of the H-1B holders through the lives of Dr. Lopa Mathur, Ketaki Desai, and Sudarshana Sengupta. These women, all having master’s or Ph.D. degrees, discuss at length the dependency forced upon them by the H-4 visa. Unable to have finances, careers, and even identities of their own, these women are obligated to put their lives on hold and be subject to the worst form of patriarchy in the U.S.

H-4 visa holders’ complete dependence on H-1 B has had innumerable negative consequences – physical and verbal abuse at home, depression, and insurmountable anxiety. Lopa Mathur, on H-4, says she faces a sense of worthlessness and often, like an alien, unwanted in society.

Mathur came to the U.S. on a dependent H-4 visa in 2007 and needed a social security number to work. She obtained a Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, and in 2015, she joined the workforce under H-4 EAD introduced by President Obama. This law allowed employment authorization for certain H-4 dependent spouses of H-1B nonimmigrant visa holders who have already filed for permanent residency. H-4 visa holders without permanent residency approval remained stranded.

The testimony of Sunayana Dumala, who struggled to remain in the U.S. as an H-4 dependent after losing her husband due to a racially motivated attack after the 2016 presidential election, tells a story of assimilation, public outcry, and the realistic availability of government assistance. The price families must pay to be accepted by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services are often not worth the constant humiliation of being labeled an alien despite the blood, sweat, and money these families pour into the United States.

Latay’s production reveals the complications of the immense backlog of green card applications for all H-1B/H-4 visas from India. Considering the political, economic, social, and personal stress migrants have received since the COVID-19 pandemic, this account provides a critical understanding of the marginalized population that remains vulnerable despite their significant contribution to the American economy.

Latay tells us that “we unintentionally tend to cater our project to our community, however, I wanted to make a movie for everyone else.” The film Alien puts the plight of the South Asians in our community into a comprehensive guide to the treacherous green card and immigration process.

Latay does mention that the 1965 immigration Act was the last in the U.S. to pass comprehensive immigration reform but does not delve into the lobbyist organizations opposing the elimination of the 7% cap, especially by the U.S. skilled workers with political support from the Republicans.

The green card backlog is the tip of the iceberg in the H-1 B category visa program issue. The gendered structure of the visa itself, disproportional taxation, fraudulent recruitments/hirings, wage theft, and casteism are just some of the few problems H-1B and H-4 visas face amid the recent tech layoffs. Alien provides a comprehensive look into the immigration experience while zeroing in on the main objective of most H-1B visa holders. However, Latay has undeniably started the conversation. South Asian representation in media no longer has to be a subpar exploration of the elite Indian minority. The South Asian community Latay documents experiences legal and economic marginalization, and their future is bleak. However, change can only come with acknowledgment of the issue first.

*************************************************

Readers

These are extraordinary times. All of us have to rely on high-impact, trustworthy journalism. And this is especially true of the Indian Diaspora. Members of the Indian community overseas cannot be fed with inaccurate news.

Pravasi Samwad is a venture that has no shareholders. It is the result of an impassioned initiative of a handful of Indian journalists spread around the world. We have taken the small step forward with the pledge to provide news with accuracy, free from political and commercial influence. Our aim is to keep you, our readers, informed about developments at ‘home’ and across the world that affect you.

Please help us to keep our journalism independent and free.

In these difficult times, to run a news website requires finances. While every contribution, big or small, will makes a difference, we request our readers to put us in touch with advertisers worldwide. It will be a great help.

For more information: pravasisamwad00@gmail.com