In a country where cinema often escapes into the fantasy world, the tapree pulls it back to reality. It reminds the audience of who they are, what they endure, and how much of their story can be told through many glasses of kadak chai.

Surat, February 14, 2026

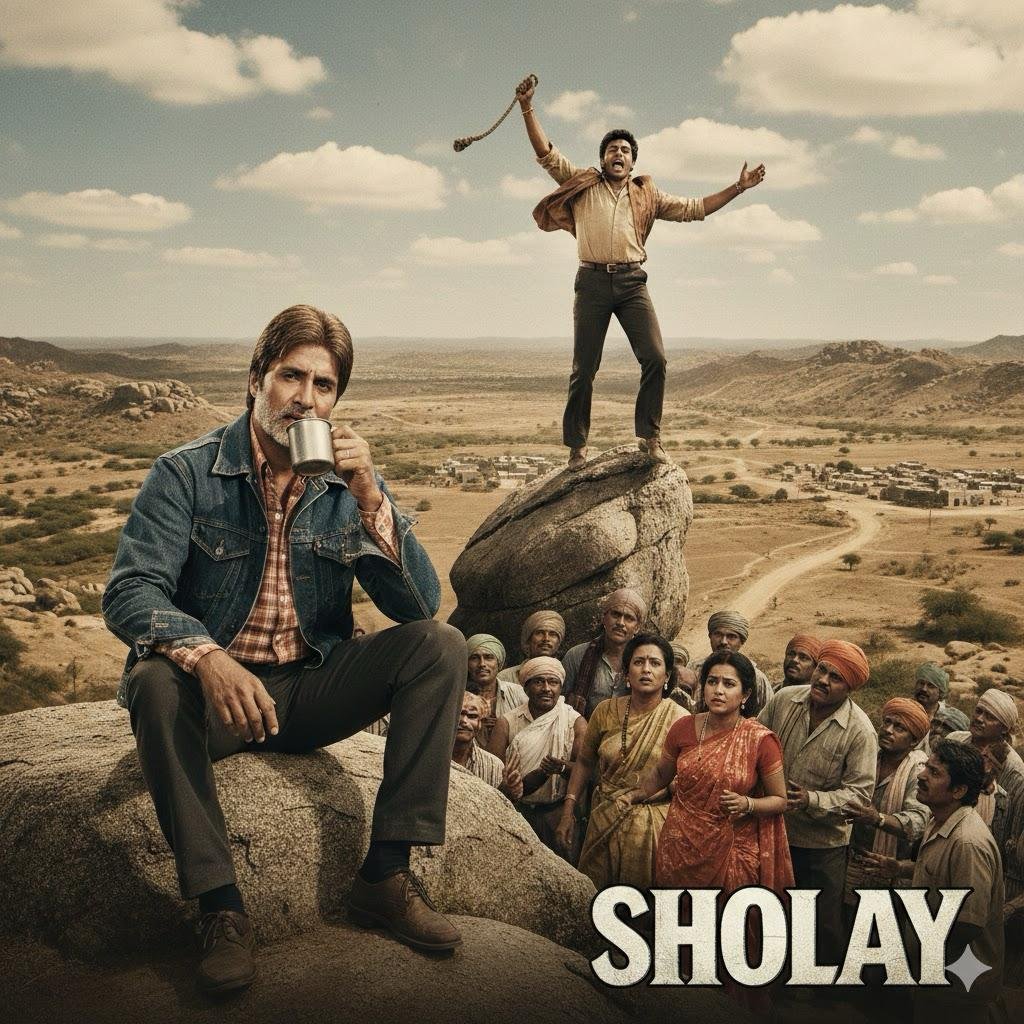

Sitting in the village tapree, Jai sips tea with a rustic slurp from the saucer holding in his right hand and the cup in his left while Basanti pleads with him to stop Veeru from comitting suicide. He watches a partly inebriated Veeru, standing on the parapet of the 30 feet high water tank, telling villagers he will jump to his death if Mausi does not allow him to marry Basanti.

In another scene, Jai chooses his words with the caution of a man walking through Ramgarh’s village square littered with cowdung. He tactfully tells Mausi a jobless Veeru’s vices — alcohol, gambling, and visiting nautch girls’ bordellos — but he ends with the one truth that Veeru has a good heart.

Through these dramatic scenes from the 1975 film Sholay where Veeru amplifies his love for Basanti while Jai narrates his friend’s character to Mausi, director Ramesh Sippy depicts ordinary peoples’ art of emotional blackmail, aspirations, and balancing friendship with affection and truth.

Many Indian directors similarly capture middleclass angst every time a film scene cuts to a tapree where kadak chai boils in a battered aluminium kettle with carbon patches. The setting remains modest, but the sub text is deep.

A tapree is more than just a stall. It is a pressure valve for the working class. The vendor pours tea with the confidence of a man who has seen every kind of customer. Behind him, a child waiter darts between tables, carrying tea in the rusted ironwire six-glass holder. The frame tells the observer everything – this is a world where survival begins early and kills the struggler early.

Invariably the chai stall becomes a newsroom of the street, where every complaint is a headline, where pleasant stories of success, woes of struggles and pathos of failures boil.

Directors use this public space to show the country’s social and economic state. When a group of jobless youths gather around a tapree, their frustration simmers with the tea. Their conversations — about cricket matches, a broken romance, a failed marriage, divorce, missed interviews, corrupt officials, rising prices or a terminal illness — become a chorus of middle‑class despair, best depicted by Director Guru Dutt through silhouette scenes of the protangist puffing his angst in cigarette smoke.

The Tapree as a mirror of work and woes

I saw similar angst in some people during my visit to a tapree on Greencity Avenue in Bhatha, Surat, yesterday evening.

Raju is a Rajasthani migrant who sells tea, biscuits, fruit cakes, cigarettes, beedis (tendu or Piliostigma racemosum leaf, tied with fragile pink thread), packaged chips, tortillas, and paan‑ghutka. His stall is a one‑man newsroom of the neighbourhood.

Raju’s customers include painters, carpenters, rickshaw drivers, maids and middleclass gentry. Workers arrive with paint droplets and dust on clothes that compromise their dignity. Most have a visibly sad countenance and pain in their eyes.

Two mechanics from Tata Motors service centre, a block away, sipped their tea while Raju spoke to me in Hindi. His voice carried the same weary honesty that directors love to capture on screen.

“Test of a genuine friend is when you ask a favour,” he said. “I told this to my friend Manish, the vada pav vendor. I asked him to find me a rental room and a loan of two thousand rupees. He bluntly refused. His tone offended me. I reprimanded him. We exchanged unpleasant words. This incident ended our six‑year friendship.”

This altercation was a scene straight out of a cinema script. Raw, unpolished, and full of angst, frustration and hurt.

A stage for broken hearts

Film directors know the tapree is where romance either blooms or collapses dramatically. Often it’s a rendezvous corner for lovers. Not always. Sometimes the boy waits for hours. The two glasses of tea get cold. The girl does not come. The vendor watches with the sympathy of a man who has seen this scene too often. The steam rising from the glass becomes a metaphor of hope dissipiating in vapour.

Raju has watched his share of such struggles and sad lives of people less fortunate than him. The constrution labourer who softly says, “Khatey me leekh lena na,” (Write it in the debt book) lest bystanders know his plight. He shrugs when he sees a young man anxiously pacing with a phone in hand. “Love problem?” he asks, as if diagnosing an illness.

A safe corner for small crimes

Taprees are a favourite haunt of people who live on the fringes of society – prostitutes, pimps, thieves and policemen. Constables come for investigative work disguised as leisure. They know well, especially Mumbai Police, petty thieves drift through taprees. Not the villains with guns, but the pickpockets, gamblers, and hustlers who live in the city’s decrepit underbelly. Directors use this space to show the intrigue of low‑level crime without melodrama. A stolen phone changes hands. A plan is whispered. A lookout pretends to sip tea.

Raju sees them too. He doesn’t judge. He only says, “Sab paapi pet ka rozi‑roti ka chakkar.” (All this daily life’s struggle for sinful stomach)

Why the Tapree endures?

The tapree is democratic. Everyone comes here — the jobless youth, the heartbroken lover, the small‑time thief, the migrant worker, the mechanic, the clerk. Kadak chai becomes the equaliser, a drink that carries heat, bitterness, and survival.

Cinema returns to this setting because it is honest. It shows India without filters. It shows people like Raju, who pour tea with one hand and carry their disappointments with the other.

In a country where cinema often escapes into the fantasy world, the tapree pulls it back to reality. It reminds the audience of who they are, what they endure, and how much of their story can be told through many glasses of kadak chai.